As I learn more and more about what to do with my stock market experiment, I’m going to be doing a lot of out-loud note taking to the world, and this one’s a goodie. I learned some good stuff about proper risk calculation, position sizing, and stop orders.

Back when I was new, stocks were always something I just bought. As if I were buying a set of paper plates or a new ukulele. I mostly bought on impulse based on… well whatever. I bought Sonicwall ($SNWL) once because I was supporting a shop that used them for their firewall. I bought Tivo ($TIVO) because it looked like some cool tech. I was supporting Align Technology ($ALGN) for work and I bought them because their Invisalign “braces” looked neato. I bought Vonage ($VG) because it was cheap and wanted to see what a penny stock felt like. I was able to exit most of these profitably though through nothing short of luck and the fact that the amount I was risking was negligible to me. The stock market money was truly fooling-around-money and if I lost all of it I might feel bad, but I’d definitely still be living just as I was. Thinking back, it’s maybe good (and bad) I didn’t land on a company offering stock options nor was even public as I didn’t heavily participate in the dot com madness. I got a lot of work done and built my capital that way just fine.

Now that I’m looking at being more methodical one of the first things that caught my eye was that I was approaching risk all wrong. In fact, my problem was that I was not approaching risk at all. I was just buying and hoping. Sometimes the stock would go up, then higher! Then higher! Then down. down again… close to where I bought it. And it would hover there. Forever. I’d forget about it. This is what happened with Apple ($AAPL) when I bought it and it seemed to be doing ok and I forgot about it for almost 5 years to suddenly have an unrealized profit of over 1000%! Other times when I bought and it went down I would panic and I’d be a wreck watching the stock tick down… down… up! down… up! up!!! back to where I bought it! SELL SELL SELL! And then I was out. This is what happened with Sun Microsystems ($JAVA, formerly SUNW). While it turned out well in both cases, I was playing with less than $500 and I could definitely be ok with that. My pain threshold was essentially the entire price of the stock because I was so emotionally invested that I wouldn’t admit I was wrong, I’d just keep holding and wishing it’d come back like a roulette gambler betting red and black only to have green come up.

A real methodology requires me to understand that I will be wrong and that I will lose money. If I can’t be perfect and always pick winners then I have to be able to deal when I pick a loser. Thus, to be more methodical I have to figure out a risk level when I buy. This is as simple as it gets, but I never, ever, did this. I know plenty of people that play the stock market and don’t do this; at least not with any formality. Thus, right now, this is the most important bit of information I have learned: Quantify risk to limit losses.

This has a number of ramifications. First, it means I have to analyze the price when I buy to find a maximum pain point if I’m wrong. Second, it means I can use this pain point to calculate my position size. Third, it means I should put in an order to close the position if I get to that pain point.

Analysis of the pain point is based on what I think will happen. This is the part that’s the hypothesis I’m testing with this stock experiment. For example, I’m going to guess a stock that has been declining for a while is bottoming out and will go up. I will calculate the pain point by figuring out how far the stock moves in an average day and subtract that from the current price, and that will be my pain point. Let’s say it’s a dollar away from where it’s trading. That means, my hypothesis that the stock is bottoming out is wrong if the stock price falls a dollar.

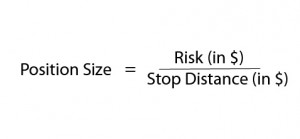

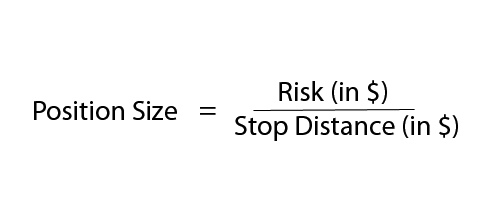

I can use that risk level to determine my position size. Since my risk is a dollar, I can risk $100 by buying 100 shares of that stock. Note, this does not take into account the price of the stock. Huh? This risk level is based on the movement of the stock and not the current price. The stock could be trading at $1.50 or $200. This position size calculation, then, is agnostic of the stock price. Of course, one should be cognizant of their stock price because while buying 100 shares of a $1.50 stock requires $150, buying 100 shares of a $200 stock requires $20,000. That math, however, works out in either case that if the price falls $1 then I would be potentially out $100. The formula is Position size (number of shares) equals Risk level (in dollars) divided by the pain threshold (also in dollars).

This quantification of risk opened up a whole different playing field for me because the way I “calculated” risk beforehand was based on the stock price: I was essentially risking everything when I bought a stock because I had no exit.

The exit is what’s known as a stop order. This is placed at the same time as the buy order (or pretty soon after) to act as the final say-so should the experiment fail. For example, if I buy the stock at $4.50 with the pain threshold of a $0.50 and a Risk level of $100, then I’d place the buy order for 200 shares ($100/$0.50) of the stock according to the position size calculation. I’ll then put in a Stop order to sell all 200 shares at the price of $4.00 (price minus pain threshold). Thus if I’m wrong, I’m out $100, if I’m right and it goes up, then.. uhh… well I should figure that out too.

The profit taking part of the equation is a bit more complicated so I’ll save it. In short, you can take off profits whenever you’re right, but how much to take off is up for debate. An easy one is to sell half the stock off at 2x pain threshold then move the stop order to the buy point. This way you lock in a profit of the Risk level (trust me, the math works out) and since the stop level’s now at the buy point, the trade is profitable and you can just move the stop up as the price goes up (sometimes called trailing the stop). There are tons of other formulas, but that’s easiest.

OK, where’s the catch? Well, you can still be wrong more than you’re right. If your risk is $100 then you could lose $100 every trade until you’re broke. Another way to do it is to calculate the risk as a percentage of your total stake– this should be done anyway, I’ve seen varying numbers for this between 1-5%. Then as you lose money your risk level goes down also. For example, if you have a $10,000 stake and your risk level is 1% of that ($100) and you lose 10 times so your stake is now 9000, your risk level of 1% of $9000 is now $90 which should be plugged into the position size calculation instead of $100.

OK… where’s the other catch? Yep, there’s another one. If you break even right and wrong you’d think you’d lose $100 then make $100, etc… but you won’t. Every trading platform charges commissions when you open or close a position. Let’s say that’s $10/trade. That means a cycle of buy/sell would be at least $20 (potentially more if you did that half-off at 2X risk thing since you’d still have to sell the rest at some time). That means you’d make only $80 and lose $120. I know! Lame! So, you can tweak your numbers to take those commissions into account and/or do what I’m doing and find a cheaper broker.

No, come on… there’s a third catch? Well this one’s up for debate, but I found this article about starting capital which paints a somewhat downer picture about how much money one can really make. The claim is that assuming a 20% annual return, a $10,000 investment stake would bring in $2000 which might be ok for some fun money but won’t pay down a mortgage; heck it won’t do one month of our current mortgage. Still, I’m undeterred — why? Because I’m not sure that 20% is right. Given the above math about position sizing, 1% of $10,000 is $100, and if I only make $100/week (that means netting one successful trade only), that’s $5000 after a year which would be a 50% gain! Someone’s math is wrong, but I won’t know whose until I start implementing.

In short, what I learned is to quantify risk. Quantifying risk leads to efficient position sizing. It also leads to logical stop orders to prevent loss. Hopefully soon I will figure out how to take gains, but first I need to figure out how to pick stocks.

I almost bought one share of Pixar before they were absorbed by Disney to have the paper certificate as a souvenir. Didn’t do it.

I’ve never seen a paper stock certificate. I’ve heard of people buying them from places like oneshare.com but the costs seem excessive: $40 on top of the share price without a frame or anything else. Then again, if I somehow make a mint off a stock I might try to get one.